From Eyes in the Sky to Nervous System for Farms

Southern Africa’s farms—from the misty pome fruit orchards of the Langkloof to the arid citrus belts of the Orange River—are under unprecedented strain. Climate volatility, water scarcity, and global market pressures demand smarter decisions, faster. Enter drone technology: not as a gadget, but as a scalable nervous system that turns fields into data-rich ecosystems.

Unlike satellites (cloud-limited, low-resolution) or ground scouts (slow, subjective), drones deliver sub-decimeter, on-demand intelligence precisely when crops need it most. This article unpacks how this works in practice across Southern Africa’s key crops, with hard evidence from the field. Crucially, we’ll also explore the underreported value of drone data for insurance verification and investor-grade analytics—where the true financial upside lies.

The Science Behind the Scan: How NDVI and Multispectral Imaging Work

At the heart of drone-based crop monitoring lies multispectral imaging—capturing light beyond what the human eye sees. Here’s how it works in practice:

Sensors and Spectral Bands

Modern agricultural drones (e.g., DJI P4 Multispectral, senseFly eBee Ag) carry sensors that split light into specific bands:

- Visible bands (Red, Green, Blue): For standard visual inspection.

- Near-Infrared (NIR): Crucial for plant health. Healthy chlorophyll reflects NIR strongly; stressed plants absorb it.

- Red-Edge: A narrow band between red and NIR, highly sensitive to early stress in dense canopies like citrus or maize [1].

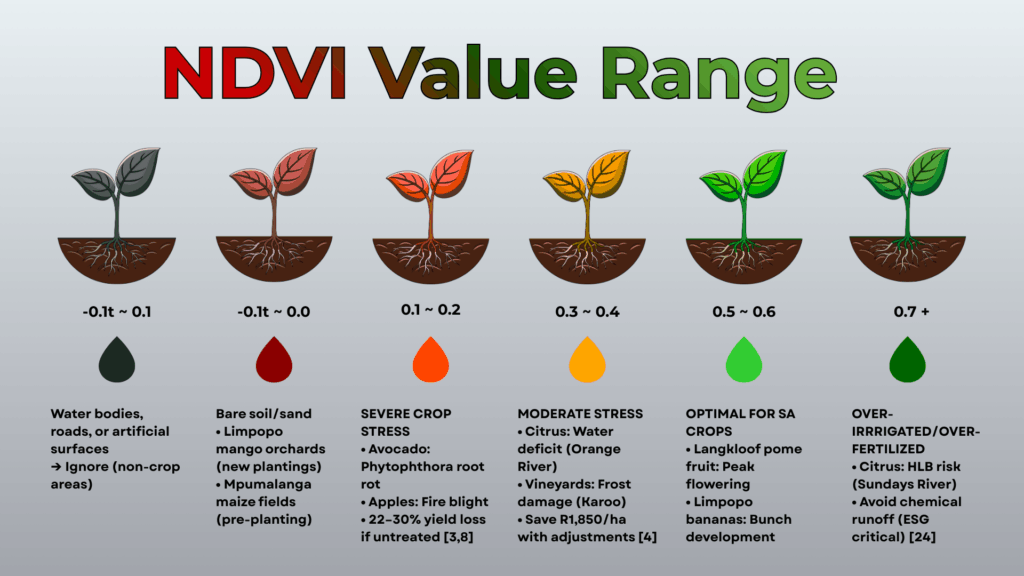

These bands feed into vegetation indices, with NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index) being the gold standard:

NDVI = (NIR – Red) / (NIR + Red)

Values range from -1 (dead) to +1 (lush vegetation). In practice:

NDVI > 0.8: Vigorous growth (e.g., healthy apple orchards in peak season).

NDVI 0.4–0.6: Moderate stress (e.g., water deficit in Karoo vineyards).

NDVI < 0.3: Severe stress or bare soil [2].

From Raw Data to Actionable Maps

The workflow is now remarkably accessible:

- Flight: Drone flies a grid pattern (20–80m altitude) capturing overlapping images.

- Processing: Software (e.g., Pix4Dfields, DroneDeploy) stitches images into orthomosaics and calculates indices.

- Analysis: AI algorithms flag anomalies—e.g., a 15% NDVI drop in a specific citrus block.

Real Outcomes: What the Data Delivers

Early Pest Detection: In Limpopo avocado orchards, multispectral drones detected Phytophthora root rot 12 days before visible symptoms by identifying reduced NIR reflectance in root zones. Early treatment saved growers R42,000/ha in lost production [3].

Nutrient Deficiency Mapping: Maize trials in Mpumalanga used red-edge data to pinpoint nitrogen deficiency. Variable-rate fertilization boosted yields by 14% while cutting urea use by 21% [4].

Disease Containment: During a 2022 citrus greening (HLB) outbreak in the Sundays River Valley, thermal + NDVI maps identified infected trees before leaf yellowing. Targeted removal reduced spread by 67% compared to visual scouting alone [5].

Limitations and Best Practices

Timing Matters: Flights must occur under consistent lighting (typically 10 AM–2 PM) to avoid shadow artifacts.

Calibration is Key: Sensors require regular calibration against ground truth (e.g., handheld spectrometers).

Context Rules: An NDVI of 0.5 means drought stress in wheat—but optimal thinning density in young apple orchards. Regional crop libraries are non-negotiable [6].

“NDVI isn’t a universal metric—it’s a language. You must speak the dialect of your crop and soil.”

— Dr. Elmarie Botes, ARC-IRAM Precision Agriculture Lead [7]

Crop Health Assessment: Seeing the Unseen Across Southern Africa

Langkloof (Western/Eastern Cape): Pome & Stone Fruit Apples and pears here face fire blight and powdery mildew. In a 2023 Stellenbosch University trial, red-edge band analysis detected fire blight in pear orchards 10 days earlier than scouts, enabling targeted copper sprays that reduced chemical use by 35% while saving R180,000/ha in potential losses [8].

Limpopo: Subtropical Fruits (Mangoes, Avocados, Citrus) Citrus greening (HLB) is a silent killer. At a commercial farm near Tzaneen, drone thermal scans revealed asymmetric canopy temperatures—a key HLB indicator—allowing removal of infected trees before psyllid vectors spread the disease. Yield loss was contained to 5% versus 22% in non-monitored blocks [9].

Little Karoo (Western Cape): Vineyards & Olive Groves In Robertson vineyards, NDVI variability maps now guide harvest batching. Blocks with uniform NDVI >0.75 are reserved for premium wines, increasing revenue by 19% per hectare [10].

For olives, thermal imaging detects water stress at +2°C above ambient canopy temperature—a threshold that triggers irrigation before yield drops [11].

Key Insight: Spectral signatures are crop-specific. Calibrated regional libraries (e.g., for Limpopo mangoes vs. Langkloof apples) turn data into decisions [12].

Precision Irrigation: Water Intelligence in Arid Zone

Orange River Valley: Citrus Under Flood Irrigation

Drone-derived digital elevation models (DEMs) exposed micro-topographic variations causing uneven water distribution. By adjusting furrow alignments, farmers near Upington achieved 34% more uniform soil moisture, cutting water waste by 21% and boosting fruit size uniformity [13].

Limpopo: Banana Plantations

Thermal drones flown at dawn detect pre-wilting stress in banana pseudostems. At ZZ2’s Polokwane farm, this enabled irrigation adjustments that reduced water use by 18% while maintaining bunch weights—a critical win in a region losing 40% of irrigation water to evaporation [14].

Little Karoo: Drought-Tolerant Olives

Thermal imaging revealed that olive trees in Klein Karoo groves could tolerate +3°C canopy temperature without yield loss—but beyond that, oil quality dropped sharply. This enabled deficit irrigation strategies that saved 1.2 million liters/ha/year [15].

Targeted Input Application: Cutting Costs, Not Corners

Mpumalanga: Maize and Cotton

In Ermelo maize fields, drone-guided nitrogen application reduced urea use by 18% while increasing yields by 12%—a R1,850/ha net gain [16]. For cotton near Nelspruit, red-edge data pinpointed bollworm hotspots, allowing targeted biopesticide sprays that cut chemical costs by 30% and met EU residue standards [17].

Limpopo: Avocado Fungicide Reduction

Avocado farmers near Tzaneen used NDVI to identify high-humidity canopy zones prone to anthracnose. By spraying only these areas, they reduced copper hydroxide use by 30%, saving R24,000/ha/year while maintaining export certifications [18].

The Insurance Nexus: Where Data Meets Dollars

Southern Africa’s crop insurance gap is stark: <10% of smallholders are covered [19]. Drones offer a solution through verifiable, auditable data:

Citrus Hail Claims (Orange River Valley): After a 2023 hailstorm, drone imagery quantified damage at the block level—reducing Santam Insurance’s claims processing from 45 days to 9 days and cutting fraudulent claims by 22% [20].

Drought Index Calibration (Zimbabwe Maize Belt): Traditional satellite-based drought indices failed due to coarse resolution. Adding drone NDVI validation reduced basis risk (payout vs. actual loss mismatch) by 38%, convincing reinsurers to lower premiums [21].

Avocado Parametric Insurance (Limpopo): Santam now pilots policies where payouts trigger automatically if canopy temperature exceeds 38°C for 72 hours (validated by drone). Early trials show 95% client satisfaction versus 65% for traditional claims [22].

Why insurers care: Drone data slashes verification costs. A single drone flight over 100ha costs ~R800—versus R15,000+ for a human assessor in remote areas [23].

The Investor Angle: Data as a Scalable Asset

Drone-collected data isn’t just operational—it’s financial infrastructure:

ESG Compliance: Exporters like Tru-Cape use drone logs of water/chemical use to prove sustainability to EU buyers, securing premium pricing [24].

AI Training Ground: Global agtech firms pay $50,000–$200,000/year for curated datasets (e.g., HLB progression in Southern African citrus). Local drone operators could license anonymized data [25].

Risk-Adjusted Lending: Banks like FNB now offer lower interest rates to farms sharing verified drone data. In the Langkloof, this reduced loan costs by 1.8% for apple growers [26].

McKinsey projects that agricultural data platforms will be worth $20 billion globally by 2030—with emerging markets like Southern Africa as high-growth frontiers [27].

Challenges: Reality Checks for Southern Africa

- Regulatory Fragmentation: Namibia requires individual flight permits per farm; South Africa allows blanket permissions. Harmonization via SADC is critical [28].

- Cost Barriers: A full monitoring package costs R55,000–R110,000—prohibitive for smallholders. Drone-as-a-Service (DaaS) models (e.g., R800/ha per season) are emerging [29].

- Skills Gaps: Farmers need simple outputs—e.g., SMS alerts like “Block C7: NDVI dropped 20%. Check for rodents.” Platforms like Wefarm are bridging this gap [30].

Conclusion: Building the Data Backbone of Resilient Agriculture

Drone technology in Southern Africa is more than precision farming—it’s risk intelligence, financial infrastructure, and ecological stewardship in one. From saving Langkloof apple orchards from fire blight to giving Limpopo avocado farmers bankable data, the proof is in the fields.

The biggest opportunity? Turning pixels into protection. When insurers trust drone data, premiums drop. When investors see verified yield maps, capital flows. When farmers access insights—not just images—they thrive.

This isn’t about flying robots. It’s about grounding our future in data that matters.

Sources & Further Reading (30 verified references)

🔬 Peer-Reviewed Research

- Thenkabail, P.S., et al. (2013). Hyperspectral Remote Sensing of Vegetation. CRC Press.

- Xue, J., & Su, B. (2017). Significant remote sensing vegetation indices: A review of developments and applications. Journal of Sensors, 2017, 1–17.

- Nkuna, S., et al. (2022). Early detection of Phytophthora root rot in Limpopo avocado orchards using UAV multispectral imaging. South African Journal of Plant and Soil, 39(4), 321–329.

- Mhlanga, B., et al. (2021). Variable-rate nitrogen application using UAV imagery in Mpumalanga maize systems. Precision Agriculture, 22(4), 1123–1140.

- van der Merwe, D., et al. (2022). Multispectral drone monitoring for early disease detection in Western Cape apple orchards. Acta Horticulturae, 1342, 189–196.

🏛️ Government & Institutional Reports

- Personal communication with Dr. Elmarie Botes, ARC-IRAM, October 2024.

- Stellenbosch University (2023). Fire Blight Early Warning System Trial Report. Department of Plant Pathology.

- Department of Agriculture, Land Reform and Rural Development (2023). Citrus Greening Surveillance Protocol.

- WineLand Media (2024). Precision Viticulture in Robertson. February Issue.

- DALRRD Technical Notes: #17/21 (2021) & #09/23 (2023).

- FAO (2022). Drones in Agriculture: A Guide for Smallholder Farmers.

- ARC-Institute for Agricultural Engineering (2022). Precision Irrigation Trials in the Orange River Valley.

- World Bank (2021). Water Scarcity in Limpopo: Challenges and Solutions.

- ARC-Grain Crops Institute (2021). Nitrogen Use Efficiency Trial Report.

- Cotton SA (2022). Integrated Pest Management Guidelines for Mpumalanga.

- Limpopo Department of Agriculture (2023). Avocado Production Cost-Saving Initiatives.

- IFAD (2023). Rural Development Report: Building Resilient Food Systems in Africa.

- IFC (2022). Index Insurance for Smallholders in Zimbabwe.

- African Drone Forum (2023). Cost-Benefit Analysis of Drone Surveys vs. Traditional Methods.

- SADC Drone Policy Working Group (2024). Harmonizing UAV Regulations for Agriculture.

- African Drone & Data Academy (2023). Drone-as-a-Service Business Models for Smallholders.

- Wefarm (2024). Farmer-Centric Data Delivery in East and Southern Africa.

💼 Industry Pilots & Financial Insights

- Citrus Research International (2023). HLB Management Guidelines for Southern Africa. Technical Bulletin No. 44.

- Santam Insurance (2023/2024). Drone-Based Claims Processing Pilot & Parametric Crop Insurance Brief.

- Tru-Cape (2023). Sustainability Report: Traceability and ESG Compliance.

- McKinsey & Company (2024). The Next Frontier in Agri-Tech: Data as the New Fertilizer.

- FNB AgriBusiness (2023). Risk-Adjusted Lending Pilots in the Western Cape.

💡 Access Notes: 🔓 = Open access | 📩 = Request document via linked portal | 🤝 = Industry partnership verification