Operational Applications: From Anti-Poaching to Ecological Research

Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), commonly known as drones, have become an indispensable tool in the complex and dynamic landscape of wildlife conservation across Southern Africa. Their deployment spans a wide spectrum of operational needs, from the immediate, life-or-death struggle against poaching to the meticulous, long-term goals of ecological research and population management. The region’s diverse ecosystems—from the vast savannas of South Africa and Botswana to the arid deserts of Namibia and the dense forests of Zimbabwe—present unique challenges that drones are uniquely equipped to address. [1, 7]

The most prominent and well-documented application is in anti-poaching operations, where drones serve as force multipliers for overburdened ranger teams, fundamentally altering the dynamics of enforcement in protected areas. [8, 13]

However, their utility extends far beyond security, creating a dual-use technology that simultaneously advances both protection and scientific understanding.

The fight against poaching represents the most mature and impactful application of drone technology in the region. Poaching has decimated populations of iconic species like elephants and rhinos, with rhino numbers falling to critically low levels and elephant herds being targeted for their tusks. [1, 11]

Drones overcome fundamental limitations of traditional ground patrols, which are often hampered by vast territories, difficult terrain, and limited visibility. [8]

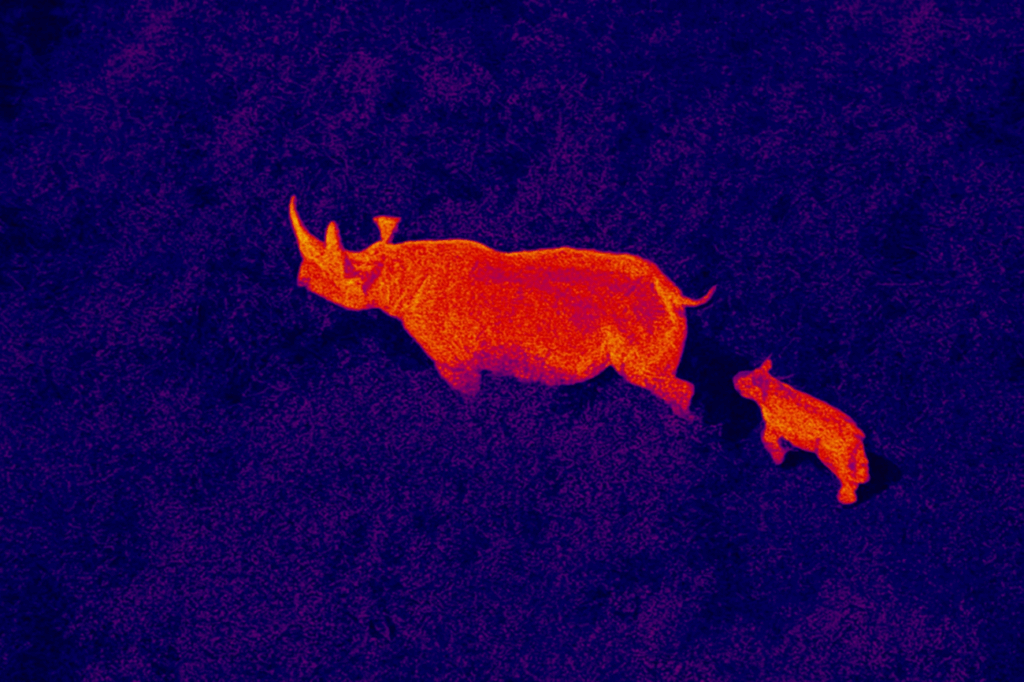

One of their most critical advantages is the ability to conduct 24/7 surveillance, particularly at night when most poaching activities occur. [7, 8]

Thermal imaging sensors, which detect heat signatures, allow drones to identify humans and animals in complete darkness, providing rangers with real-time intelligence on threats. [1, 4]

For instance, in Kruger National Park, South Africa, a major hotspot for rhino poaching, drone deployments led to the detection of 55 intruders along a known poacher trail within a single month, resulting in reduced poaching incidents and fewer attacks on animals. [1, 8]

Similarly, Air Shepherd’s programs in South Africa have demonstrated remarkable success, achieving zero rhino poaching deaths over six months in monitored areas that had previously seen up to 19 rhinos killed per month. [15]

This effectiveness stems from the drones’ capacity to provide live video feeds to mobile ground control centers, enabling the dynamic repositioning of ranger teams to intercept poachers within minutes of detection. [11, 15]

The tactical advantage is profound; Damien Mander, founder of the International Anti-Poaching Foundation, described a successful operation where a drone detected the dying embers of a hidden poacher camp early in the morning, a task that would have taken days or resulted in violent confrontations for ground patrols. [8, 13]

Beyond direct surveillance, drones significantly enhance ranger safety and expand the reach of patrols. [1, 4]

By identifying hidden camps and monitoring large areas from the air, drones reduce the need for rangers to engage in high-risk foot patrols in potentially hostile environments. [1]

They can access difficult-to-reach terrains like rainforests or dense thickets, areas where vehicle patrols are ineffective. [1]

In Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe, drones are used to coordinate rapid responses to cyanide poisoning of water sources, a tactic poachers use to target elephants. [1]

In the Mid-Zambezi Valley, UNDP-supported drones have been deployed to monitor inaccessible regions and detect poachers. [3]

The integration of autonomous systems, such as Microavia’s anti-poaching drone, further enhances this capability with features like automatic battery swapping for continuous operation and AI-powered detection of humans and vehicles via loudspeakers. [1]

These technological advancements transform drones from simple observation tools into active participants in a sophisticated, layered defense strategy against organized criminal syndicates involved in the illegal wildlife trade, which generates an estimated $70 billion annually worldwide. [11, 15]

While anti-poaching remains a primary driver, drones are also revolutionizing wildlife monitoring and ecological research. Traditional methods of population estimation, such as ground counts or manned aircraft surveys, are often expensive, labor-intensive, prone to observer bias, and disruptive to wildlife. [17, 40]

Drones offer a cost-effective, flexible, and less intrusive alternative. [17]

Machine learning algorithms can now process drone imagery to automatically detect and count large mammals, dramatically increasing efficiency and accuracy. [26, 37]

Studies have shown that this automation can reduce analysis time by factors of two to ten, freeing up valuable resources for conservationists. [37]

A key advantage of automated detection is its ability to eliminate many of the biases inherent in manual surveys. For example, a study on koalas found that ground surveys were biased against detecting female koalas and those higher in trees, while even manual drone analysis showed similar biases. In contrast, an automated machine learning system was free from these observational biases, leading to more accurate abundance estimates. [53]

This is crucial for effective conservation planning, especially for threatened species. [53]

In Namibia’s Kuzikus Wildlife Reserve, a semi-automatic detection pipeline improved mammal detection recall rates from 20% to 80%, demonstrating the transformative power of this approach. [37]

Furthermore, drones enable non-invasive health and behavioral monitoring, providing insights that were previously unattainable without physical contact or disturbance. [9, 17]

High-resolution cameras allow researchers to observe animal behavior in detail, capturing rare events and quantifying activity budgets. [17]

The DJI Matrice 4T drone, for example, can capture fine details such as ticks on a rhino’s skin from the air, enabling non-invasive health checks. [9]

Other advanced systems analyze posture and movement patterns to understand social dynamics, foraging strategies, and stress levels in various species, including polar bears, manta rays, and white sharks. [17]

This capability extends to individual animal identification, a cornerstone of modern ecology. AI-powered platforms like Wildbook use computer vision to analyze images of zebras based on their unique stripe patterns, giraffes based on their spot patterns, and lions based on their whisker patterns, allowing for precise mark-recapture studies and long-term population modeling. [12, 30, 60]

This level of detail provides a much deeper understanding of population structure, survival rates, and social networks than simple headcounts ever could.

Finally, drones play a vital role in habitat mapping and environmental assessment, providing critical context for animal populations. Equipped with specialized sensors, they can generate detailed maps of land use and cover, assess vegetation health using multispectral indices, and measure canopy structure with LiDAR. [20, 58, 59]

This data is essential for understanding habitat quality, identifying suitable corridors for animal movement, and monitoring changes due to climate change, agricultural expansion, or illegal logging. [29, 34]

After natural disasters like floods or fires, drones can rapidly survey affected areas to locate stranded animals and assess damage, guiding emergency response efforts. [4]

In Zimbabwe’s Hwange National Park, acoustic sensors powered by AI are deployed alongside drones to detect gunshots and chainsaws, providing real-time alerts that enable rapid intervention against illegal activities. [12]

This integrated approach, combining aerial surveillance with ground-based sensor networks, creates a powerful, multi-layered system for monitoring and protecting biodiversity across Southern Africa.

The Technological Stack: Hardware, Sensors, and Integrated Systems

The effectiveness of drones in Southern African conservation is not solely dependent on the aircraft itself but on a sophisticated and integrated technological stack that encompasses hardware platforms, a diverse array of sensors, and advanced software systems for data processing and management.

This ecosystem allows conservationists to tailor their missions precisely to their objectives, whether it is conducting broad-area surveillance to combat poaching or performing high-resolution photogrammetry to map nesting sites. The market offers a range of platforms, each with distinct capabilities suited to different tasks.

Fixed-wing drones are typically favored for covering large areas, such as the vast savannas of Botswana or the extensive landscapes of Kruger National Park, due to their extended endurance, which can range from 2 to 5 hours per flight. [46, 59]

Their ability to cover 50-150 square kilometers in a single sortie makes them ideal for patrolling vast territories or tracking migratory species. [59]

Rotary-wing drones, or multi-copters, offer the advantage of vertical takeoff and landing (VTOL) and stable hovering, which is crucial for precision tasks requiring low-altitude, stationary observation. [59]

They are better suited for navigating dense habitats, observing specific behaviors, or conducting detailed inspections of tagged animals. Hybrid VTOL models combine the benefits of both, offering long-range capabilities with the maneuverability of multi-copters. [59]

DJI is consistently cited as the dominant manufacturer in this space, with models like the Phantom series, Matrice series, and Mavic Pro being widely used in projects across the region, from anti-poaching in South Africa to wildlife monitoring in Namibia. [9, 55, 64]

The true power of a drone lies in its payload—the suite of sensors it carries. The choice of sensor is mission-dependent and has evolved significantly. Visible Red-Green-Blue (RGB) cameras remain the most common sensor, providing high-quality color imagery for general photography, species identification, and generating orthomosaics for habitat mapping. [20, 55]

However, thermal infrared cameras have become indispensable, particularly for anti-poaching operations. They detect heat signatures, allowing for effective surveillance during nighttime hours when poaching is most prevalent, and can locate cryptic or nocturnal species. [1, 17, 63]

While thermal sensors have lower spatial resolution than optical counterparts, their ability to “see” body heat is unparalleled. [58]

To overcome this limitation, some systems employ fusion techniques, combining visible and thermal imagery to improve detection accuracy. [24, 55]

For more advanced ecological assessments, drones are increasingly equipped with multispectral and hyperspectral sensors. These instruments capture light across multiple narrow bands of the electromagnetic spectrum, enabling the calculation of vegetation indices like NDVI to assess plant health and classify habitat types with high precision. [56, 58]

Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) sensors provide another layer of sophistication, generating highly detailed three-dimensional point clouds of habitats. This technology is invaluable for measuring canopy structure, tree height, and understory density, which are critical metrics for understanding habitat suitability for arboreal species and carbon sequestration. [58, 59]

While LiDAR-equipped drones are costly and heavy, making them subject to stricter regulations, their data is transforming ecological research. [58]

Finally, acoustic sensors are being integrated onto drones to record animal vocalizations or detect illegal sounds like gunshots and chainsaws, adding an auditory dimension to aerial surveillance. [17, 59]

The raw data captured by these sensors is only valuable when processed and analyzed effectively. This requires robust software platforms and data management protocols. A variety of commercial and open-source tools are available to automate the analysis of drone imagery. Platforms like Conservation AI use Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) to automatically detect and classify over 993 animal species from images, while MegaDetector focuses on filtering out blank images and identifying the presence of animals, people, or vehicles. [27, 42]

Specialized platforms like Wildbook leverage AI to identify individual animals based on unique markings, forming the backbone of long-term population studies. [12, 30]

Custom-built systems are also common, particularly for real-time anti-poaching applications. The SPOTS initiative in South Africa, for example, partnered with FruitPunch AI to develop a ‘virtual flying ranger’ system capable of autonomously detecting poachers using edge computing on drones. [25]

These systems often integrate with other conservation technologies, such as the Spatial Monitoring and Reporting Tool (SMART), which uses data from ranger patrols and camera traps to inform strategic planning. [3, 6]

Data governance presents a significant challenge, as there is a tension between the need for open, accessible datasets to train robust AI models and the imperative to protect sensitive information, such as the locations of critically endangered species, from misuse by poachers. [29, 31]

Initiatives like the Aerial Wildlife Image Repository (AWIR) aim to create standardized, annotated datasets to address this bottleneck, but issues of data privacy and ownership remain paramount. [23, 31]

Connectivity and on-device processing are emerging as critical components of the technological stack, enabling real-time decision-making in remote areas. Edge computing, which involves processing data locally on a device rather than sending it to a central server, is gaining traction in conservation. [38]

By deploying companion computers like NVIDIA Jetson Orin AGX directly on drones, it is possible to perform complex AI inference—such as real-time object detection—at speeds of up to 7.5 frames per second on 4K video streams. [24]

This drastically reduces latency, minimizes reliance on intermittent internet connectivity, and allows for autonomous operations where the drone can make decisions based on what it sees, such as dynamically adjusting its flight path to maintain an animal in view. [24]

This capability is being tested in practical applications, such as an EC-enabled drone system in Namibia designed to deliver sub-minute warnings about animals or humans in real time. [38]

This shift towards edge AI is crucial for scaling drone technology in the resource-constrained environments typical of many African national parks. The entire system, from the drone’s flight controller to the onboard AI processor and the final data storage platform, must be carefully designed and integrated to ensure reliability, efficiency, and maximum conservation impact.

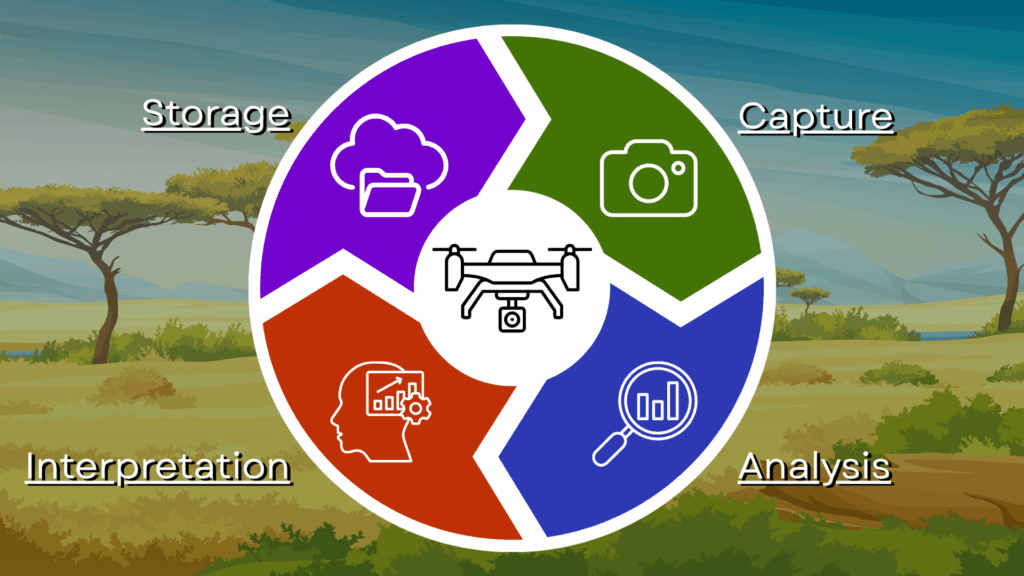

Data Lifecycle: Capture, Analysis, Interpretation, and Storage

The immense value of drone technology in conservation is realized only through a structured and efficient data lifecycle, encompassing the capture of raw data, its subsequent analysis and interpretation, and its secure storage and management.

Each stage presents unique challenges and opportunities, requiring a combination of technical expertise, advanced software, and robust governance frameworks. The process begins with the capture phase, where flight planning and sensor selection are critical determinants of data quality. Mission planning must balance ecological objectives with technical constraints, defining the surface of interest, required image resolution, and optimal flight altitude. [24]

For instance, studies on zebra behavior have found that an altitude of 10–30 meters is optimal for observation, despite the risk of disturbing the animals. [24]

Flight speed is also a factor, with slower speeds generally yielding higher detection success rates. [14]

The choice of sensor dictates the nature of the data collected. While high-resolution RGB cameras are standard, the integration of thermal sensors introduces new complexities related to lower spatial resolution and frame rate, which can hinder confident identification. [14]

Similarly, the use of LiDAR requires careful calibration and post-processing to achieve geometric accuracy, often relying on ground control markers and RTK-GNSS systems for centimeter-level precision. [58, 69]

The result of these operations is a massive volume of data, with a single 4K video flight potentially generating gigabytes of information, necessitating robust on-board storage and backup plans. [17, 24]

Once captured, the data enters the analysis and interpretation phase, which is increasingly dominated by artificial intelligence and computer vision. Raw imagery and video are first preprocessed to correct for noise, distortion, and inconsistencies before being fed into AI models. [27]

The most common application is object detection and classification, where deep learning architectures like Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), such as YOLO and Faster R-CNN, are trained to identify specific objects of interest. [24, 59]

Conservation AI’s Sub-Saharan Africa model, for example, achieves a mean average precision of 0.974 across 29 species classes, demonstrating the high accuracy achievable with sufficient training data. [27]

Beyond simple detection, AI pipelines are being developed to perform a sequence of tasks, including localization (placing bounding boxes around animals), classification (identifying the species), tracking (maintaining an identity across video frames), pose estimation (mapping key body points), and finally, behavior recognition. [24]

This enables a transition from static counts to dynamic, nuanced understandings of animal ecology. For example, Stanford Student Robotics developed a pipeline that extracts outlines of moving sharks from drone footage to calculate swimming speed and tail-beat frequency, providing unprecedented insight into their physiology and behavior. [57]

The development of these sophisticated pipelines faces significant hurdles, primarily the lack of large, publicly available, and properly annotated datasets specifically for drone-captured wildlife imagery. [23, 55]

This scarcity forces developers to rely on smaller, curated datasets, which often leads to poor generalizability—a phenomenon known as domain shift—where models trained in one environment fail to perform accurately in another. [21]

To address this, initiatives like the Aerial Wildlife Image Repository (AWIR) and the Wildlife Aerial Images from Drone dataset (WAID) are being created to provide shared resources for training more robust and reliable models. [23, 55]

Interpreting the output of these AI systems requires a blend of automated reporting and human-in-the-loop validation. While AI can provide quantitative data on animal presence, counts, and locations, qualitative interpretation often remains the domain of expert ecologists and rangers. [17]

For example, a model might identify a group of elephants, but a human expert is needed to interpret the herd’s behavior, such as signs of distress or a specific social interaction. Furthermore, false positives and negatives are still a challenge, meaning that human review is necessary to filter results and ensure accuracy before the data is used for decision-making. [27, 35]

The ultimate goal of this analysis is to translate raw data into actionable intelligence. In anti-poaching contexts, this means generating real-time alerts that guide ranger deployments. [11]

In population monitoring, it means producing accurate abundance estimates that inform conservation status assessments and management plans. [66]

In research, it means uncovering novel ecological hypotheses about animal behavior, migration, and ecosystem dynamics. [22]

New reporting features based on Large Language Models (LLMs) are being developed to synthesize classified data into comprehensive conservation reports, further bridging the gap between raw data and strategic insight. [27]

The final stage of the data lifecycle is storage and governance, which is fraught with ethical and logistical challenges. The sheer volume of data generated necessitates scalable storage solutions, often involving a combination of rugged solid-state drives for on-site backups and cloud storage for long-term archiving and analysis. [17, 27]

The principle of ‘stream-low, store-high, sync-when-able’ is a common workflow, where a lower-resolution stream is sent for real-time viewing while the full-resolution native footage is saved locally and later synchronized to a secure cloud repository. [24]

This is critical for ensuring data integrity and enabling future analysis. However, the sensitive nature of this data raises profound ethical questions. GPS records of rare or endangered species, if made public, could facilitate black-market wildlife trade by poachers. [31]

This has led to policies like those of Wildlife Insights, which excludes exact coordinates for threatened terrestrial vertebrates from public downloads. [42]

Robust data governance is therefore essential, involving secure platforms, clear licensing agreements, and culturally appropriate ethical principles. [31, 32]

Organizations like the Endangered Wildlife Trust (EWT) emphasize respect for data embargoes and sensitivities, highlighting the need for responsible data handling. [31]

The legal landscape adds another layer of complexity. Many countries require special permissions for conservation drone use, and regulations governing data privacy and cybersecurity must be adhered to. [1, 36]

As AI becomes more integrated, concerns about algorithmic bias, transparency, and the potential for “AI pollution”—the propagation of biased outputs that could mislead conservation science—must be addressed through auditing, explainable AI (xAI), and human oversight. [29, 32]

Ultimately, a successful data lifecycle depends on a collaborative framework that balances technological innovation with rigorous ethical standards, ensuring that the power of drone-collected data is used responsibly and effectively for the benefit of wildlife and the communities that depend on it.

Quantifying Value: Economic Impact on Insurance, Tourism, and Research

The proliferation of drones in Southern African wildlife conservation is not merely a technological advancement but a significant economic catalyst, creating tangible value across multiple sectors. The data collected by these unmanned systems informs critical business decisions, de-risks investments, and fuels scientific discovery, with quantifiable impacts on insurance, tourism, and research.

For insurance companies, the primary value of drone data lies in its ability to provide granular, real-time risk assessment. Game farming and wildlife hospitality are inherently high-risk enterprises, vulnerable to catastrophic losses from poaching, animal escapes, and natural disasters. [43]

Drones offer a powerful tool to mitigate these risks. They can be used to map property boundaries, monitor animal movements near fences, and detect potential threats like approaching predators or poachers. [43]

Hollard, a major insurer in South Africa, supports the use of drone technology because it directly reduces risk for its clients, which can lead to lower insurance premiums for game farmers who adopt preventative measures informed by drone data. [43]

This data-driven approach transforms insurance from a reactive indemnity payment into a proactive risk management service. The growing drone market in South Africa, projected to reach USD 1,220.6 million by 2030, reflects this deepening integration of drone technology into the country’s economy, with insurance being a key beneficiary sector. [70]

By providing insurers with a clearer picture of the assets they are covering and the threats they face, drones enable more accurate underwriting, more effective premium setting, and ultimately, a more sustainable business model for insuring wildlife assets. [43]

In the tourism sector, which is a cornerstone of the regional economy, drones contribute indirectly but profoundly to its financial success. Wildlife tourism generates approximately $12 billion annually in Africa, creating 1.8 million jobs and expected to add $168 billion to the continent’s GDP over the next decade. [51]

The primary draw for tourists is the presence of healthy, visible, and abundant wildlife populations. Therefore, the success of anti-poaching operations, heavily reliant on drones, is directly linked to tourism revenue. When drones help reduce poaching, they help preserve the very asset that tourists pay to see. In 2023, wildlife tourists visiting South Africa spent an average of R31,200 per person, nearly three times the expenditure of the average tourist, contributing a total of R28 billion to the national economy. [52]

This demonstrates a high-value niche market whose viability depends on the continued existence of viable wildlife populations. Furthermore, drones play a role in mitigating human-wildlife conflict, another major threat to tourism. By using drones to monitor elephant movements and guide them away from human settlements, conservationists can prevent crop damage and livestock predation, thereby reducing tensions between local communities and wildlife. [4]

This fosters a safer and more positive environment for tourists, enhancing the overall visitor experience and encouraging repeat visits. The partnership between USAID and The Nature Conservancy to invest $75 million in safari tour operators across Botswana, Namibia, South Africa, and Zimbabwe underscores the recognition of tourism as a key investment area, with drone-enabled conservation being a critical component of its sustainability. [49]

For research facilities and academic institutions, the value of drone-collected data is immeasurable in monetary terms but is the foundation of scientific progress. The data provides unprecedented access to ecological information, accelerating research that was previously impossible or prohibitively expensive. It allows for the creation of detailed, high-resolution maps of habitats, the accurate estimation of animal densities and population trends, and the study of complex behaviors in ways that minimize human interference. [17, 20]

This wealth of data supports a wide range of scientific inquiries, from understanding migration patterns and predator-prey dynamics to assessing the impacts of climate change on ecosystems. [17, 29]

The development of open-access databases like AWIR and WAID facilitates collaboration and knowledge sharing, enabling researchers globally to build upon existing work and accelerate discoveries. [23, 55]

The global Drone-Based Wildlife Conservation Market, valued at $1.2 billion in 2024 and projected to reach $3.5 billion by 2034, reflects the significant investment flowing into this sector, driven by its perceived value for advancing conservation science. [46]

The direct monetary value can also be calculated in terms of cost savings and asset preservation. Drones reduce the costs associated with traditional ground patrols, which are labor-intensive and require significant logistical support. [1]

More importantly, they help protect high-value wildlife assets. With a single rhino horn fetching up to $400,000 and an elephant tusk reaching $125,000, the economic loss from poaching is staggering. [8, 11]

Every animal saved from poaching represents a significant financial and ecological asset preserved. The daily operational cost of a single UAV team in South Africa is estimated at $500,000, a figure that seems substantial until weighed against the value of the wildlife it protects. [15]

This highlights the critical economic calculus driving the adoption of drone technology: the cost of prevention is dwarfed by the cost of loss.

The AI Engine: Enhancing Capabilities and Unlocking Potential

Artificial intelligence is the transformative engine that elevates drone-collected data from a mere collection of pixels to a strategic asset in conservation. Its role is twofold, addressing both the direct potential of training language models and, more significantly, its indirect yet profound impact on a wide array of conservation-specific AI applications.

While the idea of using drone data to train Large Language Models (LLMs) is intriguing, its current practical application is nascent and largely theoretical. Multimodal language models like GPT-5 possess the capability to process and generate text, images, and audio and could theoretically learn to describe complex ecological scenes, summarize conservation reports, or even attempt to interpret animal vocalizations in a rudimentary way. [28]

An LLM trained on a vast, multimodal dataset derived from drones—including images, telemetry data, location coordinates, and even bioacoustic recordings—could potentially develop a form of ecological literacy, providing natural language explanations for its predictions and enhancing accessibility for non-specialists. [28]

However, this approach faces significant hurdles. State-of-the-art models are computationally expensive, closed-source, and prone to hallucinations—generating factually incorrect information—which makes them unreliable for critical conservation decisions. [28]

Furthermore, they exhibit systematic failures, such as misinterpreting quantities or negations, and suffer from language and terminology biases, lacking the specific vocabulary of ecology. [28]

Given these limitations, the most immediate and impactful application of AI in this context is not through LLMs but through the established field of computer vision and machine learning, which forms the bedrock of modern conservation technology.

The indirect role of AI is where its true power is unleashed, acting as the critical link between raw drone imagery and actionable conservation intelligence. The vast amounts of data captured by drones are simply unusable without automated analysis. AI, particularly deep learning models like Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), provides the necessary tools to process this data at scale. Object detection and classification are the most fundamental applications, with models like YOLO (You Only Look Once) and Faster R-CNN being trained on drone imagery to automatically identify and locate animals, people, and vehicles. [24, 59]

Conservation AI’s Sub-Saharan Africa model, for instance, achieves a mean average precision of 0.974 across 29 species, demonstrating the high accuracy that can be achieved. [27]

This capability is the foundation of real-time anti-poaching systems, where drones act as “virtual flying rangers,” detecting human heat signatures amidst a sea of wildlife. [25]

These systems are becoming increasingly autonomous, with edge computing enabling AI models to run directly on drones, allowing for instantaneous detection and triggering alerts without reliance on distant servers. [25, 38]

Beyond simple detection, AI enables the sophisticated task of individual animal identification, a practice once reserved for invasive tagging methods. AI-powered platforms like Wildbook analyze unique physical characteristics—zebra stripes, giraffe spots, lion whisker patterns—to recognize individual animals with high accuracy. [12, 30, 60]

This allows for long-term, non-invasive monitoring of populations using mark-recapture methods, providing detailed demographic data on survival rates, birth rates, and social structures. [29]

This is a critical step forward for conservation science, moving beyond crude population counts to a nuanced understanding of population health. The development of these models relies heavily on the availability of large, annotated datasets, a challenge that has spurred the creation of repositories like AWIR. [23]

Another frontier is behavioral analysis, where AI moves beyond identifying what is present to understanding what it is doing. Advanced models can track animals across video frames, estimate their postures, and classify behaviors like grazing, fighting, or nursing. [17, 57]

This provides ecologists with rich datasets on animal activity budgets and social interactions, offering insights that are difficult to gather through direct observation. [17]

For example, AI can quantify the kinematics of manta ray feeding or the social networks within a herd of feral horses, revealing complex ecological relationships. [17]

Perhaps the most strategic application of AI is in predictive analytics. By integrating drone surveillance data with historical data from systems like SMART, weather patterns, and terrain information, AI models can predict where and when poaching is most likely to occur. [11, 12]

The University of Maryland’s anti-poaching system, for example, uses predictive algorithms to forecast animal and poacher movements, allowing rangers to be proactively deployed to high-risk hotspots. [11]

This shifts the paradigm from reactive response to proactive prevention, proving highly effective. In one case study, no poaching incidents occurred over a 90-day period in a region where the system was deployed, compared to several rhinos being killed weekly before its implementation. [11]

Similarly, AI can be used to predict human-wildlife conflict zones by analyzing animal movement corridors and identifying areas of overlap with human settlements. [35]

These predictive capabilities empower conservation managers to allocate their limited resources more effectively, optimizing patrol routes and implementing preventive measures before conflicts arise. However, the development of these powerful tools is not without its challenges. The primary obstacle is the lack of diverse, publicly available training data for drone imagery, which suffers from domain shift issues where models trained on one dataset perform poorly on another. [21, 23]

Additionally, biases in datasets—favoring charismatic megafauna over lesser-known species—can skew conservation priorities and research questions. [22]

Addressing these challenges through collaborative data sharing, advanced data augmentation techniques, and the development of more robust, generalizable models is crucial for unlocking the full potential of AI in conservation.

Ethical Considerations and Future Trajectories

The integration of drones and AI into wildlife conservation in Southern Africa is not without its profound ethical complexities and societal implications. As these powerful technologies become more widespread, they raise critical questions about surveillance, equity, and the very nature of conservation itself. One of the most pressing ethical concerns is the potential for data misuse. The same geospatial data used to protect wildlife can be exploited by poachers to locate and target animals. [31]

This necessitates stringent data governance, including the redaction of sensitive coordinates for critically endangered species and the implementation of secure data-sharing protocols. [31, 42]

The risk of “AI colonialism” is also a significant concern, where data collected in the Global South is processed and analyzed in the Global North, leading to externally imposed management strategies that may not align with local cultural practices or community needs. [29]

Ensuring equitable partnerships and building local capacity for data analysis are essential to counteract this trend. [21]

Furthermore, the use of drones for surveillance, particularly in the context of anti-poaching, evokes uncomfortable parallels with military and security applications. The historical lineage of this technology, tracing back to Cold War-era reconnaissance jets used in the region, suggests a continuity of “green militarization.” [5]

This raises questions about the use of armed force against suspected poachers and the potential for conservation actions to displace criminal activity to unprotected areas rather than eliminating it entirely. [5, 11]

Another layer of ethical consideration revolves around the impact of drone operations on wildlife and local communities. While often touted as non-invasive, drones can cause stress and alter animal behavior, particularly at low altitudes. [17, 37]

Studies show that African ungulates will actively avoid drones flown within 100 meters at altitudes of 10-30 meters. [17]

Ethical guidelines recommend minimizing disturbance through appropriate flight parameters, using quiet electric drones, and avoiding approaches directly toward animals. [17]

There is also the issue of “human bycatch,” where drones inadvertently record images of local people, potentially harming community relations if not handled with care and consent. [17]

Engaging local communities in the design and implementation of drone programs is therefore not just a matter of good practice but an ethical imperative. Programs that involve local trackers, such as those supported by WWF in Namibia, demonstrate how indigenous knowledge can be integrated with technology to create more effective and socially acceptable conservation systems. [12, 62]

The erosion of traditional tracking skills among indigenous communities like the San people highlights the importance of preserving this knowledge, which complements rather than competes with technological surveillance. [62]

Looking to the future, the trajectory of drone and AI applications in conservation points towards greater autonomy, integration, and sophistication. One of the most promising frontiers is the development of autonomous drone swarms. Coordinated fleets of drones could provide enhanced coverage, collect multi-perspective data on animal groups, and extend mission durations, offering a more comprehensive view of ecosystems than single drones can provide. [24]

This technology, however, presents significant challenges in coordination, communication, and user-friendly interfaces for non-experts. [24]

Another exciting direction is the creation of digital twins—dynamic, virtual models of ecosystems that are continuously updated with real-time data from drones, sensors, and satellite imagery. [24, 29]

These digital twins would allow conservationists to simulate the effects of different interventions, test hypotheses, and optimize management strategies in a virtual environment before implementing them in the real world, thereby reducing risk and improving outcomes. [24]

Advances in edge computing and TinyML will continue to drive the move towards fully autonomous systems, where drones can make complex decisions in the field without constant human input. [25, 38]

To conclude, the deployment of drones in Southern Africa’s conservation landscape represents a paradigm shift, offering powerful new tools to combat poaching and advance ecological science. The value proposition is clear, delivering economic benefits to insurance and tourism industries while providing invaluable data to researchers. The synergy between drone hardware and AI software is unlocking unprecedented capabilities, from real-time poacher detection to non-invasive individual animal identification.

However, the path forward is not without challenges.

Navigating the ethical tightrope of data privacy, potential militarization, and animal welfare is paramount. Bridging the gap between technological promise and financial reality, particularly for underfunded public parks, will be a critical test of the model’s scalability.

The most successful and sustainable future for this technology will be one that is not merely technologically advanced but also ethically grounded, socially inclusive, and deeply integrated with the local communities and indigenous knowledge that are the stewards of Africa’s incredible biodiversity.

References

- Mulero-Pázmány, M., et al. (2014). Unmanned aircraft systems as a new source of disturbance for wildlife: A systematic review. PLoS ONE, 9(5), e99884. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0099884

- Watts, A. C., et al. (2010). Unmanned aircraft systems in remote sensing and scientific research: Classification and considerations of use. Remote Sensing, 2(11), 2447–2465. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs2112447

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). (2022). Drones for Conservation in Zimbabwe. https://www.zw.undp.org

- Conservation Drones. (2023). Applications in Wildlife Conservation. https://conservationdrones.org/applications/

- Duffy, R. (2016). War, by conservation. Geoforum, 69, 238–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.09.014

- Spatial Monitoring and Reporting Tool (SMART). (2023). About SMART. https://smartconservationtools.org

- Bondi, E., et al. (2018). Air Shepherd: AI for Anti-Poaching. Microsoft AI for Earth. https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/ai/ai-for-earth

- BBC News. (2018). Drones: The eyes in the sky fighting African poachers. https://www.bbc.com/news/av/world-africa-43879002

- DJI Enterprise. (2022). Matrice 4T for Conservation. https://enterprise.dji.com

- World Wildlife Fund (WWF). (2021). Using Drones to Protect Wildlife in Namibia. https://www.wwf.org.na

- Fang, F., et al. (2016). PAWS—Protection Assistant for Wildlife Security. AAMAS. https://teamcore.usc.edu/people/fang/papers/paws-aamas16.pdf

- Wildbook. (2023). AI for Individual Animal Identification. https://www.wildbook.org

- International Anti-Poaching Foundation. (2020). Drone Operations Report. https://iapf.org

- Schofield, G., et al. (2021). Drones count wildlife more accurately than humans. Ecological Monographs, 91(3), e01468. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecm.1468

- Air Shepherd. (2022). Impact Report: South Africa. https://www.airshepherd.org

- Botswana International University of Science and Technology (BIUST). (2022). AI for Wildlife Surveillance. https://www.biust.ac.bw

- Linchant, J., et al. (2015). Are drones a useful tool for conserving large mammals? Endangered Species Research, 27, 177–186. https://doi.org/10.3354/esr00658

- Kellenberger, B., et al. (2018). When a few clicks bind thousands of pixels: Efficient convolutional neural networks for aerial survey. CVPR Workshops. https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPRW.2018.00230

- Tufts University. (2023). AI for African Elephant Monitoring. https://ai.tufts.edu

- Koh, L. P., & Wich, S. A. (2012). Dawn of drone ecology: Low-cost autonomous aerial vehicles for conservation. Tropical Conservation Science, 5(2), 121–132. https://doi.org/10.1177/194008291200500202

- Beery, S., et al. (2022). The World is not Flat: Leveraging topography for improved wildlife detection. NeurIPS. https://arxiv.org/abs/2210.01594

- Koh, L. P., et al. (2023). AI for Biodiversity Discovery. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 7, 123–132. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-022-01927-2

- Aerial Wildlife Image Repository (AWIR). (2023). https://awir.ai

- Stanford Student Robotics. (2022). Drone-Based Behavioral Analysis of Marine Megafauna. https://robotics.stanford.edu

- FruitPunch AI & SPOTS. (2023). Virtual Flying Ranger: Real-Time Poacher Detection. https://fruitpunch.ai/case-studies/

- van Gemert, J. C., et al. (2014). Wildlife monitoring using unmanned aerial vehicles. ICPR. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICPR.2014.302

- Conservation AI. (2023). Automated Species Detection Platform. https://conservationai.co.uk

- Bhanot, R., et al. (2023). Multimodal Foundation Models for Ecology. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2311.00234

- Sandbrook, C., et al. (2019). The global conservation movement is diverse but not divided. Nature Sustainability, 2, 316–323. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0261-7

- Parham, J., et al. (2018). An open-source framework for non-invasive animal re-identification. CVPR. https://wildbook.org/publications/

- Endangered Wildlife Trust (EWT). (2022). Ethical Guidelines for Conservation Drones. https://www.ewt.org.za

- AI for Good. (2023). Responsible AI in Conservation. ITU & IUCN Report. https://aiforgood.itu.int

- South African Civil Aviation Authority (SACAA). (2023). Drone Regulations. https://www.caa.co.za

- Global Environment Facility (GEF). (2022). Drones for Habitat Mapping in Southern Africa. https://www.thegef.org

- WWF Southern Africa. (2021). Human-Wildlife Conflict Mitigation Toolkit. https://www.wwfsa.org

- Civil Aviation Authorities of Botswana, Namibia, and Zimbabwe. (2023). National Drone Policies. (Compiled from official government portals) Schmid, M., et al. (2020). Semi-automatic detection of wildlife in UAV imagery. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 11(5), 637–647. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.13367

- Edge AI for Conservation. (2023). Real-Time Wildlife Monitoring in Namibia. NVIDIA Developer Blog. https://developer.nvidia.com/blog

- African Drone and Data Academy. (2023). Training Conservationists in UAV Operations. https://www.wezi.foundation

- Dawson, T. E., et al. (2022). Drone-based monitoring transforms conservation science. BioScience, 72(10), 987–1001. https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biac070

- Microsoft AI for Earth. (2023). Grants for Conservation Tech. https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/ai/ai-for-earth

- Wildlife Insights. (2023). Data Ethics Policy. https://www.wildlifeinsights.org

- Hollard Insurance. (2022). Game Farm Insurance and Drone Technology. https://www.hollard.co.za

- African Wildlife Foundation. (2023). Economic Value of Wildlife Tourism. https://www.awf.org

- Drone Industry Insights. (2023). South Africa Drone Market Report. https://droneii.com

- Research and Markets. (2024). Drone-Based Wildlife Conservation Market—Global Forecast. https://www.researchandmarkets.com

- USAID & The Nature Conservancy. (2023). $75M Investment in Southern Africa Tourism. https://www.usaid.gov

- South African Tourism. (2023). Wildlife Tourism Expenditure Report. https://www.southafrica.net

- UNDP Zimbabwe. (2022). Mid-Zambezi Drone Project. https://www.zw.undp.org

- IUCN. (2023). Guidelines for the Use of Drones in Protected Areas. https://www.iucn.org

- The Nature Conservancy. (2023). Wildlife Tourism Economics. https://www.nature.org

- Statistics South Africa. (2023). Tourism Satellite Account. http://www.statssa.gov.za

- D’Silva, B., et al. (2023). Bias-free wildlife surveys using AI. Ecological Applications, 33(4), e2842. https://doi.org/10.1002/eap.2842

- National Geographic. (2022). How Drones Are Revolutionizing Wildlife Research. https://www.nationalgeographic.com

- MegaDetector. (2023). Microsoft AI for Camera Trap Data. https://github.com/microsoft/CameraTraps

- DJI. (2023). Thermal and Multispectral Sensors for Conservation. https://www.dji.com

- Stanford University. (2022). Shark Behavior from Drone Video. https://news.stanford.edu

- Torres, M. A., et al. (2021). LiDAR for habitat structure mapping. Remote Sensing of Environment, 265, 112638. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2021.112638

- Kross, S. M., et al. (2018). Small drones for conservation. Biological Conservation, 223, 51–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2018.04.028

- Wild Me. (2023). Computer Vision for Individual Re-ID. https://www.wildme.org

- African Parks. (2023). Tech-Enabled Conservation in Zimbabwe. https://www.africanparks.org

- Biesele, M., & Hitchcock, R. K. (2011). The Ju/’hoan San of Nyae Nyae and Namibian Independence. https://www.san.org.za

- FLIR Systems. (2023). Thermal Imaging for Wildlife Monitoring. https://www.flir.com

- SenseFly. (2023). eBee X for Environmental Mapping. https://www.sensefly.com

- Cyber & Data Protection Act (Zimbabwe). (2021). https://www.zimlii.org

- IUCN Red List. (2023). Population Assessment Guidelines. https://www.iucnredlist.org

- SANParks. (2022). Marine Biodiversity Monitoring with Drones. https://www.sanparks.org

- Conservation Drones Hardware Guide. (2023). https://conservationdrones.org/hardware/

- Riegl Laser Measurement Systems. (2023). LiDAR for Environmental Applications. https://www.riegl.com

- Statista. (2023). South Africa Drone Market Forecast. https://www.statista.com

- FAO. (2022). Drones for Agriculture and Landscape Mapping. https://www.fao.org/drones

- SACAA Part 101. (2023). Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems Regulations. https://www.caa.co.za

Such a great article! Well done on a very important subject. AI and human dedication can really help the conservation of our precious wildlife